From here on X.

In 1940, British pilots were dying without ever being hit by the enemy.

The cause was purely technical.

They were flying the Spitfire—already an exceptional aircraft in terms of aerodynamics and maneuverability—but one critical flaw remained: engine fuel supply under strong negative acceleration.

During a steep dive to escape a Messerschmitt, negative G-forces caused fuel to surge into the carburetor.

The mixture instantly became too rich.

The engine lost combustion, spluttered, then cut out completely.

A few seconds were enough to turn an agile fighter into a stationary target.

German aircraft, equipped with direct fuel injection, retained full power in dives and pull-outs.

The tactical advantage was real, measurable, and deadly.

RAF engineers were well aware of the problem.

But the “ideal” solution required a complete redesign of the Merlin engine—unrealistic in the midst of the Battle of Britain.

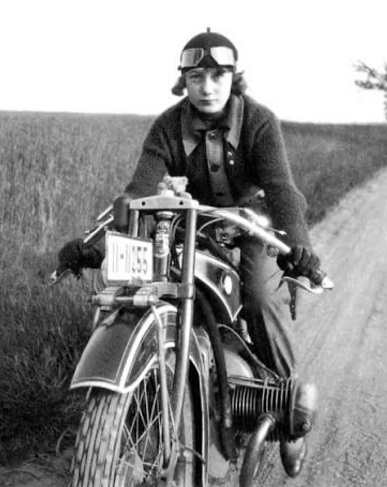

That is where Beatrice “Tilly” Shilling came in, an aeronautical engineer and recognized specialist in high-performance mechanics.

Accustomed to pushing engines to their limits in motorcycle racing, she approached systems not as abstract theory, but under real extreme conditions.

Rather than redesigning the engine, she carefully analyzed the fluid dynamics of the fuel delivery system.

Her diagnosis was simple and rigorous: the issue was not combustion, but an instantaneous excess of fuel flow.

She calculated a critical threshold.

The engine had to receive enough fuel to maintain maximum power, but never enough to flood the carburetor under negative G.

Her solution was brutally effective.

A simple brass flow restrictor, drilled with millimetric precision, installed upstream of the carburetor.

A passive component, with no moving parts, no failure risk, dimensioned exactly to the Merlin’s requirements.

She personally validated the device, then traveled from airbase to airbase to have it installed.

No committees, no delays—tests, measurements, results.

Once in place, the engine remained fueled during dives.

Spitfires could maintain power, follow the enemy through vertical maneuvers, and finally exploit their full aerodynamic potential.

Officially, the device became known as the “R.A.E. restrictor.”

On the airfields, pilots simply called it “Miss Shilling’s orifice.”

It was not an elegant solution in the academic sense.

It was a performant, robust, immediately operational solution.

Exactly what war demanded.

Without flying an aircraft or firing a single shot, Beatrice Shilling turned a critical disadvantage into a measurable tactical gain.

A striking example of what engineering can achieve when guided by technical mastery, sound calculation, and the courage to act quickly.

©️ Eric Fdl / Imperial War Museum / National Geographic

History

📷©️Wikipedia