John McNaughton Epley M.D.FEBRUARY 8, 1930 – JULY 30, 2019

The following story is a must read…. Epley maneuver for vertigo was invented by Oregon doctor

Please follow that link and read the story there.

My short commentary is below followed with a few excerpts from the article reproduced simply out of fear that this valuable tale may disappear off the net.

Originally published Dec. 31, 2006, with the headline: Doctor and invention outlast jeers and threats

By JOE ROJAS-BURKE, The Oregonian

**********

Commentary by Tim Wikirwihi….

Epic!

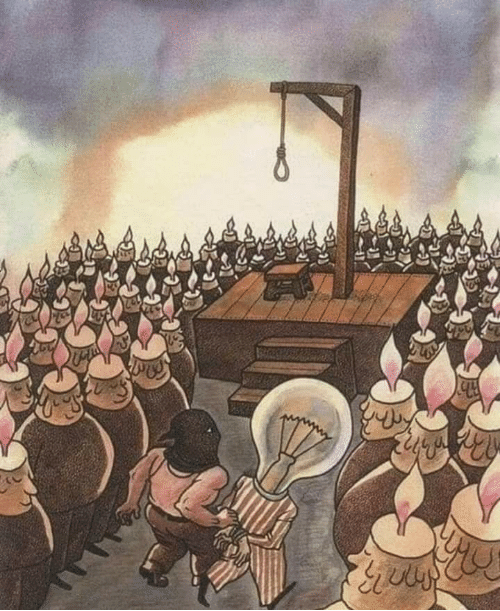

This is a perfect example of how Forward thinkers are treated like fools by the Backward and entrenched status quo… and how innovators meet with hostility from the establishment.

It also shows why People should not simply leave their own health concerns or those of their friends and loved ones in the hands of ‘the Experts’… or trust that they are telling you the whole truth!

It is also informative that this sort of behavior is especially prevalent in the fields of science exposing the fallacious yet carefully crafted myth that the scientific fraternity is peopled with enlightened and objective thinkers who are especially open to progressive ideas… the opposite is true… science is infested with narrow minded and Dogmatically opinionated drones… who are more likely to resist progress than speed it.

And this being so my friends… you had better be prepared to swim against the flow of ‘accepted opinions’ if you want to more closely understand the truth.

Quote:

“In a pause between patients, Epley reflected on the reasons other doctors refused to accept his findings for so many years.

“If I look back at medical school, much of it was misinformation,” he said. “Physicians learn to just do the routine, to do the accepted things — don’t go too far out. They’ve got so much to lose if they stick their neck out.”

Rest in Peace Dr Epley.

Tim Wikiriwhi

Excerpts….

“He is a doctor and innovator. Years ago, he took aim at a medical curse that has disabled millions of people and defied treatment. He came up with a cure that was astonishingly simple. No surgery. No pills.

Now, think: Would his colleagues cheer his stroke of ingenuity by spreading the news — and practice — of the treatment to relieve suffering?

No. Inexplicably, they rejected him, ridiculed him, heaved accusations that threatened his license to practice medicine.”

“John Epley’s stooped shoulders and gentle eyes gave him a turtlish look. He wore a thickly knotted necktie and wrinkled sport coat. No amount of combing could tame the stubborn cowlick in his short hair.

His audience of ear surgeons muttered skeptically and shook their heads. Few at the October 1980 meeting in Anaheim, Calif., believed Epley’s claim to have developed a cure for the most common cause of chronic vertigo.

In any given year, tens of thousands of people seek treatment for the disorder’s strange, crippling attacks. Provoked by a casual tilt or turn of the head, the victim’s surroundings whirl. The eyeballs twitch involuntarily. Nausea overwhelms the senses. On-and-off bouts may torment a sufferer for years.

Physicians were baffled. The best they could offer as treatment was a drastic last resort: surgically destroying nerves to the inner ear, impairing patients’ balance and possibly their hearing.

Epley proposed an elegant alternative.

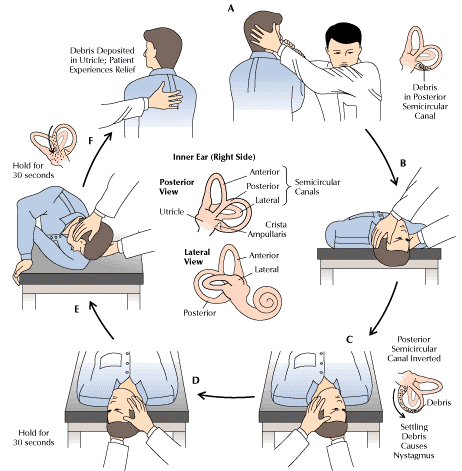

His talk concluded with a demonstration, a young woman acting as his patient. Epley and his research collaborator, audiologist Dominic Hughes, began by tilting the woman flat on her back, her head hanging over the end of an exam bench. Hughes cradled her head in his hands and rotated it about 45 degrees to his right, then he and Epley rolled the woman’s head and shoulders back to the left in a counterclockwise move that ended with her face down. In a final move, Hughes and Epley lifted the woman to a sitting position.

And that was it.

By then, audience members were walking out. One doctor stomped up to Epley and slapped down a comment card before exiting. He’d scrawled, “I resent having to waste my time listening to some guy’s pet theory.”

”

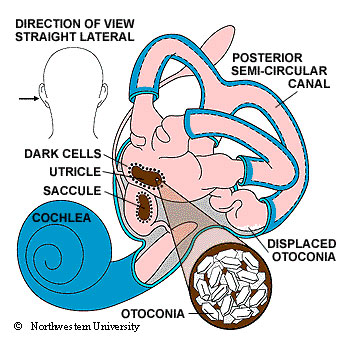

To maintain balance, the brain coordinates messages from the eyes, from muscles pulling against gravity and from motion sensors inside the inner ear’s maze of fluid-filled canals.

Another researcher had reported finding chalklike particles in the inner ears of vertigo patients and proposed that these particles clumped onto ears’ motion sensors to trigger false sensations of motion. But the hypothesis failed to explain the on-again-off-again nature of positional vertigo: If particles stuck on sensors, why did dizziness ever go away?

Epley and Hughes reasoned that the particles must float freely. Head movements might shift them, causing a siege of dizziness until the particles settled or shifted. It might be possible, they figured, to move the particles where they wouldn’t cause mischief. Since the particles are denser than inner-ear fluid and sink, gravity could do the work.

Hughes used plastic tubing to build a model of the inner ear. To simulate loose particles, he put BBs in the coiled tubes. He and Epley flipped and turned the hand-size model as they might a kid’s puzzle, to work out a sequence of moves to reposition the tiny metal balls.They began testing the moves on people straightaway, tilting and rolling them on an exam bench. Odd as the treatment sounded, frustrated patients were keen to try it.

The first two or three subjects seemed to gain immediate relief. At first, Epley wasn’t too impressed. The condition often clears up by itself, he recalls reminding himself. He didn’t know whether he had made any difference.

But when the treatment cured several more patients, including one who had endured dizziness for a decade, he and Hughes realized they’d hit upon a great discovery.

Hard sell

In Portland, some of Epley’s colleagues were so skeptical that they began to question his medical skills. Some doctors stopped referring patients.”

“In front of hostile crowds, he kept presenting his findings. Ken Aebi, a medical supply salesman in Portland who’d become Epley’s friend, felt helplessly embarrassed for him. Epley struggled at the lectern, reading too much from notes and occasionally wandering off on tangents. Some doctors rolled their eyes. Others laughed openly.”

Desperate patient

At an emergency room in 1995, a doctor couldn’t figure out the cause of a sudden attack of vertigo that struck Joseph Delahunt.

He had crawled from the living room of his North Portland house out to his car so that his wife could drive him to the hospital. Delahunt hung his head out the window and vomited most of the way. An Air Force veteran in his mid-50s, he was healthy and active — selling real estate and practicing yoga — until the attacks started.

Delahunt consulted his family doctor, then tried a neurologist and an ear, nose and throat doctor. They prescribed motion-sickness drugs and other medicines that didn’t help much. One told him he’d have to learn to live with the “benign” condition. None mentioned Epley’s treatment. His wife discovered it on the Internet.

Delahunt’s condition worsened. To avoid unbearable, spinning nausea, he sat as still as he could in a reclining chair. For nearly three months, he left the recliner only to go the bathroom.

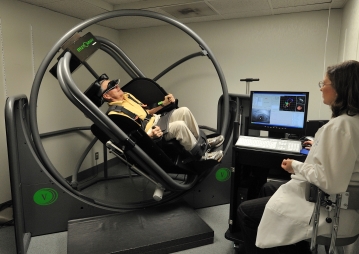

At Epley’s office, an assistant helped Delahunt down a long hallway to a gray-walled room with closed blinds. An ungainly apparatus filled much of the room. Inside a giant steel ring hung a padded chair that reminded Delahunt of an ejection seat. Motors, gears and drive-chains were rigged to flip and twirl the chair like a carnival ride.

Delahunt stepped up to a platform and into the chair. An assistant clipped straps across his chest and ankles. She covered his eyes with a bulky mask. It contained a video camera to track his eyes. She clipped a vibrator behind his ear. It buzzed gently, more lightly than a cell phone on vibrate.

“Are you comfortable?” the assistant asked. Delahunt nodded, grateful for the Valium he’d taken.Epley fingered a joystick controller to tilt the chair back until Delahunt was face up. A flick of the joystick rotated Delahunt like a barbecue skewer. On a black-and-white computer display, Epley monitored his patient’s eyes for a characteristic twitching movement triggered by positional vertigo. He repeated the series of calibrated tilts and whirls. Then he swung the chair upright and face-forward.

No waves of vertigo struck when Delahunt moved his head. The nausea had cleared. He stopped taking the medications other doctors prescribed and resumed his life.

Threat to livelihood

In Portland, many doctors still dismissed Epley as a crank.

The conflict flared into a crisis in 1996. The Oregon Board of Medical Examiners notified Epley that he was under investigation for alleged unprofessional conduct.

His medical license and livelihood were on the line.”

“Epley’s accusers, two Portland physicians, testified that Epley was administering the nerve-deadening drugs recklessly, based on inadequate diagnostic testing.

Epley’s main defender, a Harvard-affiliated specialist from Boston, described Epley as “a forward thinker who has been right virtually every time he stuck his neck out.”

Litzenberger left no doubt whom she found most credible, portraying the board’s medical experts as hostile, one-sided and ill-informed. In the summer of 2001, Litzenberger dismissed all claims.”

“By then, a review article in the prestigious New England Journal of Medicine had credited John Epley as the inventor of the “treatment currently recommended” for positional vertigo. In clinical trials, about 90 percent of patients were cured by a single treatment. Doctors applying treatment around the world referred to it as the “Epley maneuver.”

Victory….

“At 76, Epley sees patients three days a week. He spends the two other days of the workweek at Vesticon. His daughter’s startup has already launched development of two of Epley’s other inventions.

In a pause between patients, Epley reflected on the reasons other doctors refused to accept his findings for so many years.

“If I look back at medical school, much of it was misinformation,” he said. “Physicians learn to just do the routine, to do the accepted things — don’t go too far out. They’ve got so much to lose if they stick their neck out.”

2019 epilogue

Three years after this article was published on the front page of The Oregonian, Dr. John Epley had a stroke and retired. He died in July 2019.